There are over 250 minerals in Elba’s mountains. The island has been mined from the Etruscans to the Tuscans and we’re heading to the mineral park in Rio Marina to learn about the practicalities of extracting them. But this must wait as we wind our way around the main road, because we’ve just got to stop off at picture-perfect Porto Azzurro.

Leisure craft waft on a gentle sea, the houses are those boiled sweet colours: tangerine, sherbet lemon, peach, blue. Porto Azzurro is a pretty enough Mediterranean town, with its fair share of cafés, boutiques, squares and graceful church spires.

Though one backstreet ceramic workshop is different. Ceramic bees (the symbol of Elba), jugs and plates are embedded into walls.

Its courtyard is adorned with paintings, lush plants and ceramic treasures in a cornucopia of creativity.

A russet, conical mountain, topped by a giant iron-worked cross, marks the sanctuary of the Madonna di Monserrato, perched on the rocky outcrop. The sanctuary was built there to replicate the Catalonian Montserrat by grateful duke, José Pons y León, who prayed to the Madonna when caught in a Sirocco storm near Elba.

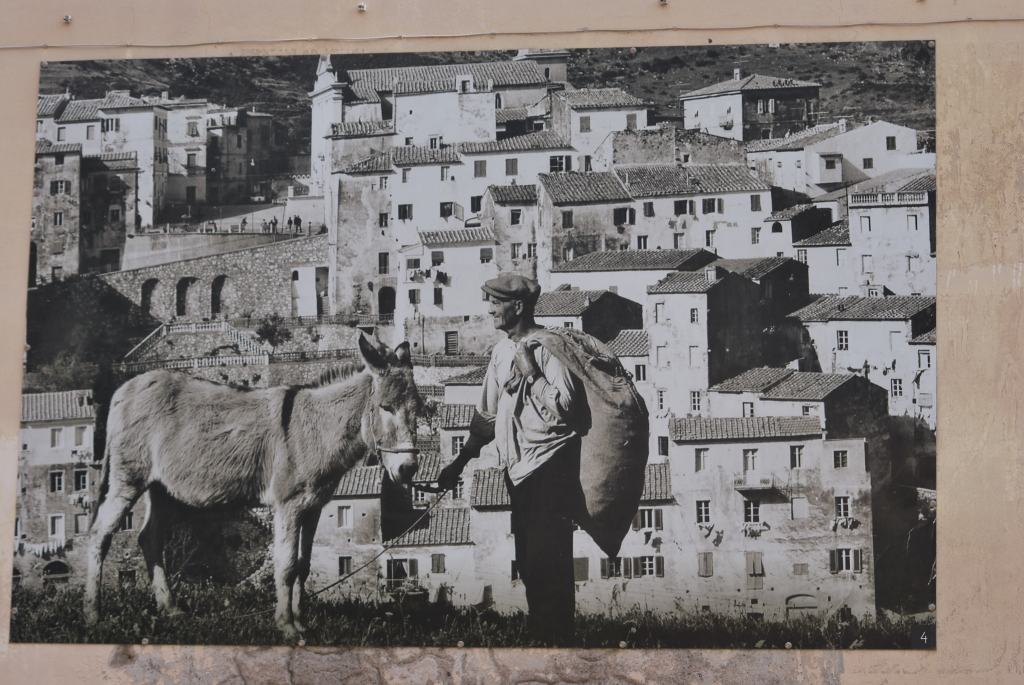

Rio nell’ Elba is one of those villages that clings to the mountain side. We climb up the narrow stone stairs to the centre. The town is famous for its iron mines dating back to the Etruscan period. The houses huddle together, as if they’re part of the mountain itself, with the cobbled streets and dark alleyways.

I love an outdoor photo gallery and the black and white prints from the 1960s of cool young men hanging out round the fountain, or hard at work mining, are somehow elegiac.

At Rio Marina, we walk out along the harbour wall to the old tower built by the Pisans, the island of Cerboli blue and misty in the sea, and return by the 19th Century terracotta clock tower.

At the Museo Minerario there’s a treasure trove of glittering earth crystals.

When the open-air mineral park’s tourist train arrives, I’m wistful as I remember all the ones we went on with our children when they were younger.

As the train struggles up the mountain, twisting around hair-pin bends, I have a sudden vision of us plunging into the sea below. From here, though, you can see the old rusting pier where they shipped the iron ore to America.

At first, nature seems to have reclaimed the mountain, with cheerful, yellow bloomed Fleabane rioting along its slopes. But as we pass the rusted machinery you can see the extent of our human impact on the natural world around us.

We pull up at the huge open cast mine, which closed in the 1980s. The mountain is scarred but strangely beautiful: the stones red with iron-ore; creamy white with calcium carbonate; shining black or gold with iron pyrite; a greeny-blue with malachite.

The fun starts when the driver produces a bucket of hammers and picks, along with tough bags. We can mine our own crystals and minerals. The three boys beside us almost crack up with excitement.

Soon the whole mountain resounds with frantic digging, and I have to admit we get caught up in the joy of crystal hunting as much as any of the children.

Leave a comment